The City of Darkness under the City of Light

Millions of Bones Beneath the Streets of Paris

I don’t remember when I'd first heard about the Catacombs of Paris, a series of underground chambers containing the neatly arranged bones of six million former Parisians, but it was high on the list of things I really wanted to see in Paris.

So one day, after lounging around for the better part of the morning, we took the Paris Metro (which was pretty easy to use) to the Denfert-Rochereau station, conveniently right across the street from the entrance to the Catacombs. As soon as we climbed up the steps to the street level, we knew we'd be in for a bit of a wait — the queue to get into the Catacombs was pretty long.

Queue for entering the Catacombs (the small green building).

We walked around the corner and down the block to stand behind all the other people waiting to see huge piles of bones. For the better part of an hour we shuffled along as people slowly trickled in to the Catacombs. Finally, we entered the little green building and paid our admission (€10 for adults, kids under 18 are free). Then we waited ...

Digital display of people in the Catacombs

... because only 200 people are allowed into the Catacombs at a time. The current number of people currently exploring the Catacombs is tracked with a digital counter mounted on the wall above the entrance, and when this number clicked down to 195, the attendant gave us a nod, and we started our journey down ...

130 Steps Down

Going down ...

... the 130 steps of a dizzying spiral staircase. It seemed to take a lot longer than it probably did. At the bottom, there’s a gallery explaining the history of the place — how it started as a limestone quarry before becoming the world’s largest ossuary.

Limestone Tunnels Under Paris

Most of the buildings in Paris are built from limestone, and almost all of that limestone was quarried from deposits underneath the city. As a result of all this mining, there are now more than 200 miles of tunnels underneath Paris.

Of course when one goes digging holes underneath a city, one should not be surprised when houses fall into those holes. And that’s what started to happen in the late 18th century. So in 1774, King Louis XV set up the an organization known as Inspection of Mines that started to reinforce and strengthen these underground passages.

Dim corridors.

From the informational gallery, we walked down long corridors carved from the limestone. It's chilly down here, a little damp, and it smells like earth. At different points along our walk, we noticed signs and directional markers in the wall.

Reference markers.

There’s also a crude black line along the ceiling, supposedly so those who came to pay respects to the dead wouldn’t get lost in the labyrinth of tunnels.

Follow the black line to the bones.

After walking for about ten minutes or so, we turned a corner and saw some amazing sculptures of the Port-Mahon Palace (also known as St. Phillip’s Castle) on the island of Menorca carved out of the limestone.

Port-Mahon Palace, carved in intricate detail.

A sign nearby explains these were carved by a quarryman named Décure sometime around 1777. Décure had been held prisoner in the fort opposite the palace for a long time, and he carved these from memory.

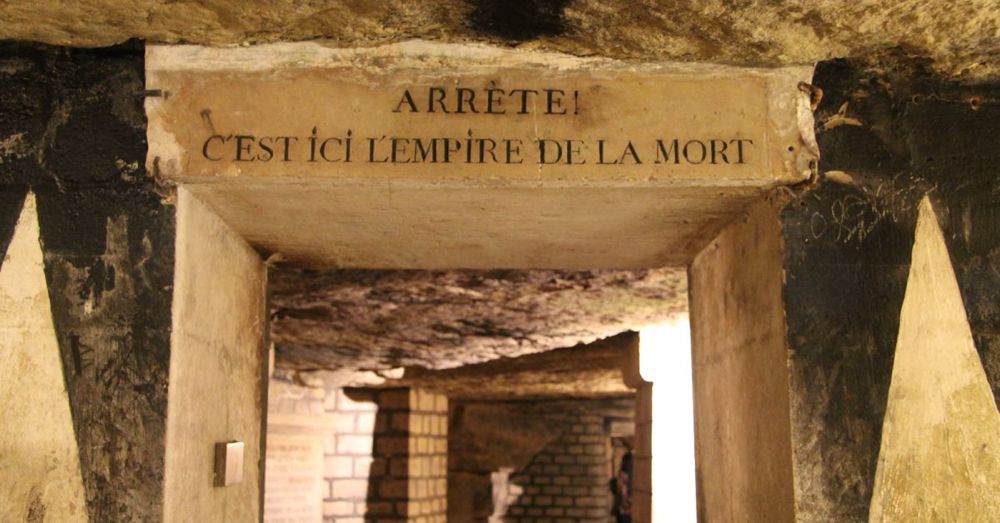

The Empire of Death

A short distance beyond the carvings, we arrived at a doorway with Stop! This is the Empire of Death! (or something very similar in French) inscribed over the entrance. We enter — and yet there are still no bones. Instead, there’s another plaque.

A brief history of the catacombs.

This one explains, as near as I can decipher, that these catacombs were established in 1786 under the order of Mr. Thiroux, the inspector general of the quarrymen. They were restored and increased in 1810 under the order of Louis-Étienne Héricart de Thury, head of the Inspection of Mines.

So why are all these bones down here?

Before Napoleon III started his comprehensive redesign of the city around 1850, Paris was not a nice place to live. There are a few reasons for this (like the possibility of your house collapsing into the ground), but one of the biggest was the overflowing cemeteries, which held the accumulated dead of 13 centuries.

By all accounts, the worst of these was the excessively overcrowded Holy Innocents Cemetery. To make room for new dead bodies, existing graves were often exhumed and the bones were stacked inside mass graves (and the fat from the decomposed bodies was used to make soap and candles).

The smell of decaying bodies was overwhelming and the health conditions were appalling. Something had to be done — the city needed a place to move all the bones that had accumulated there over the centuries. So they worked out a plan to move all the buried corpses from Holy Innocents and other burial sites inside the city to the newly renovated tunnels beneath the city.

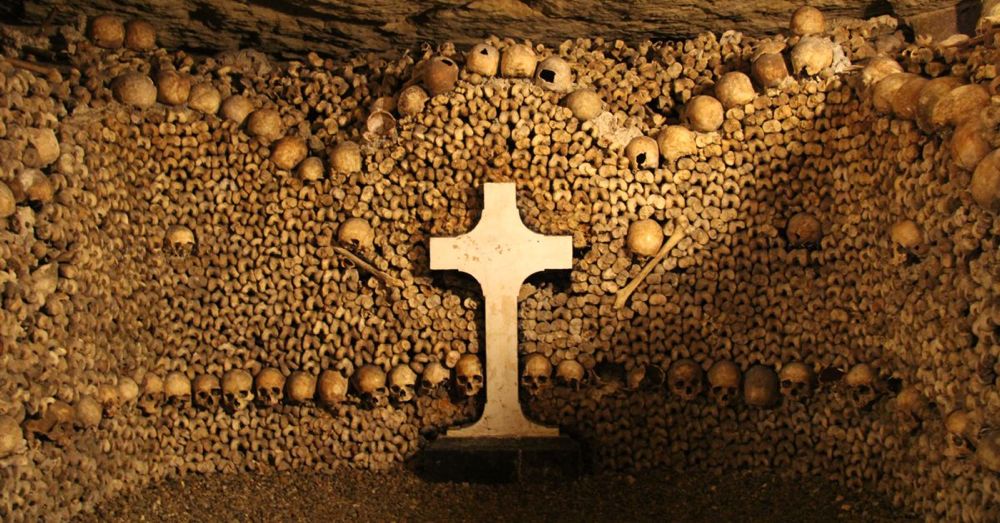

Emptying the Paris cemeteries of the exhumed dead and transferring the bones to their new home in the former limestone quarries took two years. At first it was a mess with bones piled anywhere. But, as the plaque above indicated, de Thury took steps to organize the bones into a proper mausoleum. When it was done, it looked a lot like it does today.

Corridor of Bones

The corridors were lined with bones, artfully and respectfully arranged. And while it wasn’t as macabre as the decorative arrangements at the Sedlec Ossuary in Kutná Hora, it was just as fascinating.

Bones

We only saw a small portion of the entire ossuary. In many places locked and barred iron gates prevented access to even more corridors that extended deep into the caverns beyond.

Chronological marker.

Every so often we came across a sign marking a certain pile of bones. Sometimes these signs contain bits of poetry, but usually they serve as some kind of chronological indicator of when the bones were placed or organized.

A chapel of bones.

In addition to the seemingly endless rows of neatly stacked bones, some alcoves feature more intricate designs, like chapels, crypts, and even bone-covered pillars.

Crypt of the Sepulchral Lamp

By the time we’d reached the exit, we’d spent about 45 minutes down in the Catacombs and walked nearly two kilometers through the chilly limestone caverns filled with the bones of former Parisians.

83 Steps back up

Although it took 130 steps to get into the crypts, it only takes 83 to get back up another spiral staircase to the sunny daylight of Paris. We’d walked more than two kilometers under the city of Paris, but we’d emerged about 500 meters to the southwest of where we’d started.

The Catacombs of Paris: A 15-Minute Strange but True Tale

by Melissa Cleeman

If you want to know more about the Catacombs of Paris, this nice, short (only 20 pages!) history of the place is available for Kindle for $0.99.

Tom Fassbender is a writer of things with a strong adventurous streak. He also drinks coffee.